Speaking of Pushing Past the Pain ..... Alberto Salazar & Dick Beardsley ..... Marathon MadnessNovember 8th, 2010

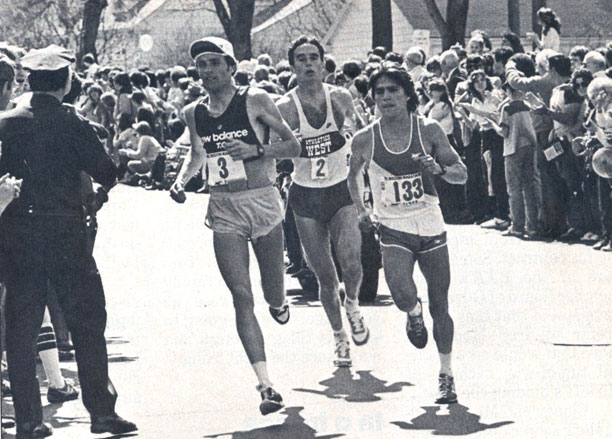

Boston 1982 - The Duel In The Sun

by Don Allison

In the universal scheme, a decade is a veritable blink of an eye. In the world of marathoning, where fame is fleeting, a decade can seem like a lifetime. Surely to Alberto Salazar and Dick Beardsley, two athletes who staged an epic duel in the 1982 Boston Marathon, one that has not been and is not likely to be repeated for years to come.

By 1982, 24 year old Alberto Salazar was in the midst of an unprecedented streak of dominance in the world of long distance running. Predicting victory and backing it up in his marathon debut (New York City 1980), Salazar went on to record-breaking performances in cross country, track, and road racing. His outspoken style often aggravated rivals, while his running earned their respect. Clearly, he was the man to beat in any race he entered.

In sharp contrast, Dick Beardsley had quietly crept up on the consciousness of the running community. The soft spoken midwesterner concentrated on the marathon, steadily improving his personal best in each of his first twelve 26 milers, culminated by an eye opening 2:09:36 in the 1981 Grandma's race in Minnesota. Unknown at the time, Beardsley's sharp focus and intense training for the '82 Boston marathon had elevated him to the level of his more celebrated rival.

To Salazar, competing in the Boston marathon was a natural progression in a stellar running career. As a talented and precocious teenager from Wayland, MA, he often challenged the seasoned international runners of The Greater Boston Track Club, earning him the moniker 'rookie'. An all-American career at Oregon University followed. Salazar incurred a knee injury in his final year there, but overcame it to snag the final spot on the 1980 USA Olympic 10000 meter team. The US team never made it to Moscow and Salazar turned his attention to the marathon.

The New York City marathon had been the sole province of the legendary Bill Rodgers from 1976, when it moved to the five boroughs from Central Park. As the 1980 race approached, Salazar responded to queries about his readiness by predicting a time of 2:10. As good as his word, he crossed the line first in 2:09:40. His second marathon, a year later back in New York, resulted in a much celebrated world record 2:08:13, a time later rescinded when the course turned up 146 meters short. The red hot Salazar captured second in the world cross country championships in March of '82 and a week prior to Boston ran a time of 27:30 in a 10000 meter challenge race in Eugene. He was unsure about running his hometown marathon despite his father's exhortations to do so. Salazar remembers: " I felt very confident. I was unsure of whether I was going to run until a few days before. I ran hard 10K a week before and had a slight hamstring tear. I felt I had a shot at the world record based on my finish in the world cross country and the 10K time." Recovery proceeded a pace and a mid week announcement indicated Boston was on.

There was no such equivocation with Beardsley. As a high school runner in Minnesota, he received a unique graduation gift from his father. " He gave a round trip paid ticket to run the Boston Marathon. I never dreamed at the time that when I finally ran years later, it would be as a contender for first place." A bit surprised by his own success, he set his sights on Boston by hooking up with coach Bill Squires, renown for prepping elite marathoners for the rigors of the hilly trek from Hopkinton. A virus two months prior to the race slowed Beardsley, but the rest period left him feeling refreshed and ready. " It was definitely the best thing for me. I got back into training and set a PR for 10K (29:12) in Atlanta. It felt incredibly easy."

Beardsley arrived in Boston two weeks before the marathon. After running the first half of the course at 5:30 pace in full sweats, he awoke the next day to find a full foot of snow on the ground. Undaunted, he headed to the heartbreak hills with Squires and completed the scheduled workout into the teeth of a noreaster. Nothing was going to interrupt final preparations. He says, " I was very excited. I never felt more ready for a race. I was also happy to see Al was running. I wasn't sure he was running until I saw him get off the plane." Friendly and accessible to everyone, Beardsley arrived in Boston with a refreshing and candid approach, saying "I'm thrilled to be here and I'm going to go out and give it my best shot."

Dawning of April 19 brought groans to most of the competitors. The marathon was scheduled for noon, yet by nine, the weather was already comfortable for shorts and T-shirts and getting warmer. This was fine for Beardsley, who did much of his training in Atlanta and considered himself a good hot weather runner. Salazar, on the other hand, spent the winter in rainy and cool Oregon. This did not diminish his confidence. He felt ready to run. Beardsley was not an unknown commodity to Salazar. " I knew he was going to be tough. He was focused on Boston. He had been flying back and forth to Boston to train on the heartbreak hills."

As is usually the case in Boston, a large pack of runners blasted through the early downhill miles. Despite the weather, mile one was clocked in 4:35. Regarding the conditions, Salazar remembers, "It didn't feel that warm. Although it was in the sixties, it was very dry, sort of like Arizona." One by one the challengers dropped off the relentless pace. Four time winner Bill Rodgers let go at sixteen miles and by the time they turned at the Newton firehouse on to the hills, it was a two man race. Beardsley was unfazed by the situation, gaining confidence with every stride. " I knew no one had been with him before at that point in a marathon. I felt great and tried to break him on the hills." Salazar was clearly in for a major challenge, but insists he didn't feel the pressure. " I knew that if I got over the hills without him breaking me, there was no way I wouldn't win, unless I tripped and fell or something. I felt my track background would be the difference."

As the duo passed Cleveland Circle and closed in on the final miles, the crowd was becoming aware that a race for the ages was in progress. No major advantage was gained by either on Beacon street until they reached the Eliot Lounge landmark with less than a mile to go. Beardsley was looking the fresher of the two, as his competitor's countenance took on a strained and pale look.

Despite this, Salazar was not about to relinquish his title as the world's finest marathoner without a battle. A circus atmosphere enveloped the race. A growing entourage of police motorcycles flanked the runners, attempting to ward of the enthusiastic crowds spilling out on to the course for a better view. It was at this point that Beardsley felt his hamstring go. In a heartbeat, Salazar gained a sizable advantage. Beardsley remembers the moment:

" So many thoughts went through my head. At first I had trouble running and told myself that second place was not so bad. Then I thought, 'I've done nothing but eat sleep and drink Boston for the last six months, I have to keep trying.' Miraculously, a pothole Beardsley stepped in righted his hamstring. " I shifted into a higher gear, cutting the lead until I pulled even. I remember him looking back with a horrified look on his face." He adds, " Then I made my biggest mistake. I was relieved just to have caught up. I should have gone right by him, but I didn't." What followed was the oft cited "motorcycle incident"

As the course turned on to Ring road for the finish in front of the Prudential building, (the course has since been altered to a finish further down Boylston street) one of the motorcycles allegedly forced Beardsley to a wide turn, costing him precious distance. Beardsley dismisses the incident, saying " I never thought that was why I didn't win." Rather, it was the true champion in Alberto Salazar that emerged. Drawing upon his last reserves, he sprinted to the finish, holding off Dick Beardsley by two ticks of the clock before staggering across the finish, utterly spent. The two embraced about twenty yards beyond the finish line. Said Beardsley, "You ran a hell of a race." Replied Salazar, "You had me hurting." The winning time of time of 2:08:53 was an afterthought then, but would increase in importance as the days, months and years passed following the race. The 2:09 barrier, bettered by the pair on a warm afternoon, would remain unbroken by US marathoners to this day.

The contrast in the physical condition of the two runners was clearly evident in the initial moments following the finish. Salazar made a half hearted appearance to receive his laurel wreath, before retreating to the medical area for some much needed attention. The animated midwesterner who had nearly stood the world of marathoning on its ear remained at the finish line laughing and talking to the media.

The drama was not over although third place finisher John Lodwick was several minutes up the road. Doctors attending to Salazar saw his condition deteriorate. Completely dehydrated, a chill cooled his body temperature to 88 degrees. Several liters of IV fluids were required to stabilize his condition. Recalls Alberto, " I felt decent immediately afterward, but started to feel feint at the awards ceremony. I went to the underground garage where they gave me fluids. Have you ever had a cramp in your foot? It felt like I had a cramp in my entire body. In retrospect, I surely didn't drink enough during the race. I took no water at all over the last eight miles." He candidly traces some problems he encountered in later years to that race, saying, " I've never said this before, but I feel that one race had a lot to do with my health problems in later years. I feel I permanently damaged my thermo regulatory system on that day. Although I went on to run well on the track that summer, I never was the same and it all went downhill after that." In perhaps the greatest testimony to the importance of the victory, he expresses no regrets. "If asked whether it was worth it, I would have to say yes. It means a great deal to have won that race."

Remarkably, or perhaps not, Beardsley was also never quite the same, despite the fact that he finished in relatively good shape. " I probably did some stupid things afterwards. I raced hard when I probably shouldn't have. I just couldn't say no to the race directors who invited me to races." Not surprisingly, Dick remains upbeat about the marathon today. "I have no regrets at all. There was no loser on that day. It doesn't matter that I finished second. To have run so well against somebody I respected so much was enough. I'll not forget that day - it left such a positive mark on my life. I have absolutely no regrets. If I had it to do over, I wouldn't change a thing." A fitting conclusion to a classic indeed.

Hear Dick Beardsley tell it in his own words!